Teaching in Health: The How-To and Its Relevance in the Scope of Clinical Education.

Introduction

The teaching in health series will be a 2-part article. The first part is about learning how to teach with its pedagogy techniques, and the second part is about putting it all together for a presentation. In this article, I will be talking about how to create and run a short presentation/lesson with a focus on teaching in health. Bear in mind that this is only the basics as education and learning techniques would take years to master to which I am only a beginner. However, I feel confident to give a small presentation and apply what I have learned to teach students about an aspect of health. I find this topic very interesting and invaluable, especially in a hospital setting where I could present a case study to a whole medical team. Learning how to teach enables the teacher to become better communicators, which is useful in physician to patient communication. I feel I have become a better learner, and I definitely can appreciate all the time and effort teachers and lecturers put into their teaching so that a lot of information can be delivered effectively.

Part 2 demonstrates how we presented our assessment by using everything we had learned previously. My colleague and I had to prepare and present 2 lessons to a group of medical students. Each lesson would be running for 20 minutes with a topic of our choice relating to medicine. I also had to present a case study through a ZOOM meeting for 20 minutes to a second-year medical students. I thoroughly enjoyed the experience and learning the pedagogy techniques, especially when Bloom’s Taxonomy was involved. Maybe one day, when I am experienced enough, I could give a whole 50-minute lecture to an entire cohort of medical students.

Who are we teaching & what factors are affecting teaching?

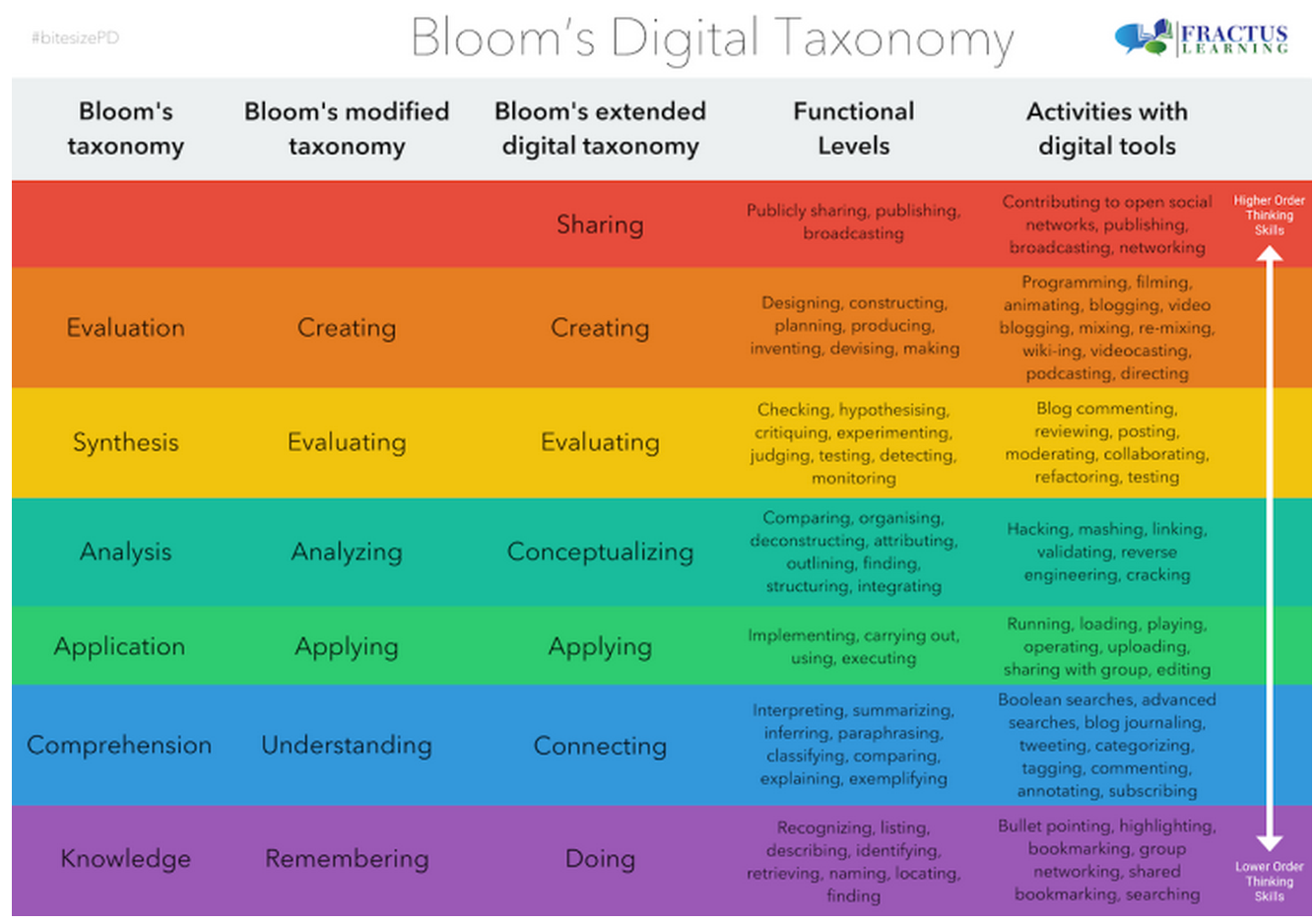

There has been a gradual shift in teaching over the past 50 years. From traditional style teaching which was passive-like learning, teacher focus, subject knowledge, didactic to a more of a current style teaching which includes active-style learning, student focus, variation in pedagogy techniques, collaborative and personal development. I believe the internet and technology have managed to drastically change the learning style over the years to more proactive and active-style learning, which is excellent! In a way, I am grateful to have learned (currently still learning) medicine through the 2020s as there are many different types of learning techniques compared to what my father had to learn (who also did medicine) in the mid 1980s where computers and the internet were non-existing.

So, to who are we teaching? Before starting on the lesson plan and getting the learning outcomes, the teacher needs to know his/her audience. What are the learners’ overall age? Are they locals? Do they have a lot of experience? Are they experts in their fields? For example, I would approach my teaching style very differently if I had to teach or present in front of a group of medical students compared to a group of consultants, registrars and interns. One group is much older, more experienced and are experts in their fields. Hence, know your audience as it will influence how you are going to teach.

A teacher should be aware of what influences their students on their learning. These could be: prior knowledge, individual factors, social factors, developmental factors, affective factors and motivational factors (the list could be much longer but I decided to focus on these). Prior knowledge is advantageous as it links what your learners know to what is being taught now. It was found that learning needs to connect to existing knowledge so that it can be remembered. For example, when teaching about the hormones being released from the pituitary gland, a prior understanding of the anatomy of the pituitary gland would be useful or maybe its embryology origin.

Individual factors influence the dynamics of how learners learn or how they collaborate. This may include learners who are willing to ask questions, work in groups, who are confident with one another and contribute to the lesson. Sometimes when a teacher is giving a lesson, having learners or students who are entirely silence could be a challenge for the teacher. A learner who is willing to answer the questions may push over the edge the other student’s confidence to also ask questions. You may be surprised by how many students who want to ask questions but are too embarrassed to ask. There is nothing more uncomfortable than having blank faces and unengaging students. Social factors describe more about the social background of the learners. This could be their culture, religion, ethnicity, social status in the community, rural/urban, student leavers/mature age students, and local/international students. Knowing the social factors of your learners can help them relate to the teacher and the content being given. This influences which pedagogy style or techniques may be used. Imagine teaching a social group that has never used a computer; there would be a challenge regarding the usage of programs. We can group individual and social factors as they both influence the dynamic of a group of learners.

Developmental factors are fascinating. These factors are dependent on generations which includes Silent Generation, Baby Boomers Generation, Generation X, Millennials and Generation Z. Each of these generations was brought up very differently and each have different vision of the world with different virtues. For example, teaching baby boomers with the latest visual learning or the use of social media for a project could be a challenge. Have a look at your audience and prepare adequately as each generation think and learns differently.

Affective factors involve self-efficacy. It is about how a student perceives themselves about their learning and their ability to succeed. Being at university, this can induce a high level of stress and anxiety. A student with high self-efficacy can understand where they went wrong if they did not do so well in a test; they work harder, are more focused and put a lot more effort. A student who has a low self-efficacy would struggle to accept when they get bad marks and would get frustrated. They would often give up and question their existence of being in a complicated program. In a way, it describes how resilient a student is towards learning and how they work under constant pressure.

Motivational factors can be divided into 2 categories. These are extrinsic, which is about external motivational factors, and intrinsic, which is about the person. This includes their personal choice and their control over their learning. Extrinsic factors are not the best way to approach learning. A learner, when using extrinsic factors, would use the marks, exams, impress their peers or avoid failing as motivators. An intrinsic approach is more about a desire to learn, to be better, to understand and to thoroughly enjoy themselves as they are passionate about a subject or degree. I find myself to do both.

Principles of teaching & learning outcomes

There are many principles and theories involving teaching, and the amount of knowledge in the literature is astounding. However, a few of these teaching principles caught my attention. Malcolm Knowles talks about how adults learn best when they are actively able to participate in the given activities. It was also found when adults can share experience, knowledge and relate to the topic, produced a more fundamental understanding of what is being taught. Adults also enjoy seeing their progressions along a particular course; this involves getting feedback and being on a marking scale. Malcolm concludes that adults do best when they have control of their environment and see the bigger picture of why they are learning a topic. For example, when you can relate congestive heart failure and its symptoms to a real patient with congestive heart failure, this experience adds a lot of relevance to the student understanding and learning.

Below is an infographic about Malcolm Knowles and his theory on adult learning. Andragogy means “the method and practice of teaching adult learners; adult education”. This infographic image was found on e-learning infographic.

Essentially Malcolm Knowles talks about active learning where the learners or students learn by doing and experiencing learning as a process. This is far more effective than passive learning where knowledge is transferred from the teacher to the students. Passive learning is not the most effective way to transmit information. So how do we successfully transmit knowledge to a student/learner? This is where a teacher needs to build a scaffolding structure as knowledge must be built on and not transmitted (just like passive learning). To build a scaffolding structure a teacher must create a solid base. Throughout the teaching, by using different pedagogy techniques, the scaffolding structure will become taller as knowledge is purposefully being added through active learning. See what works best for you as there are many theories and principles such as Malcolm Knowles on Andragogy, Bloom’s Taxonomy, Gardner's Theory of Multiple Intelligences, Kolb's Learning Styles and Experiential Learning Cycle and so on.

Learning outcomes

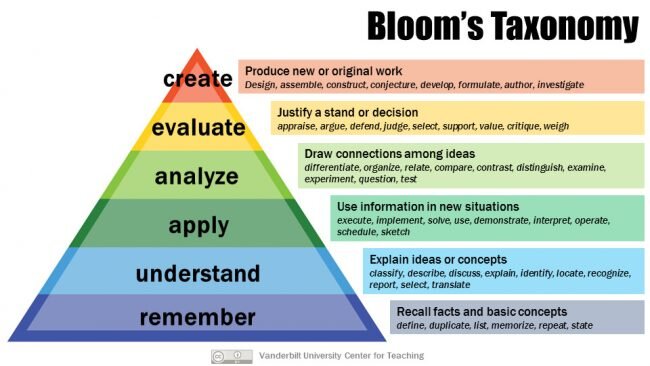

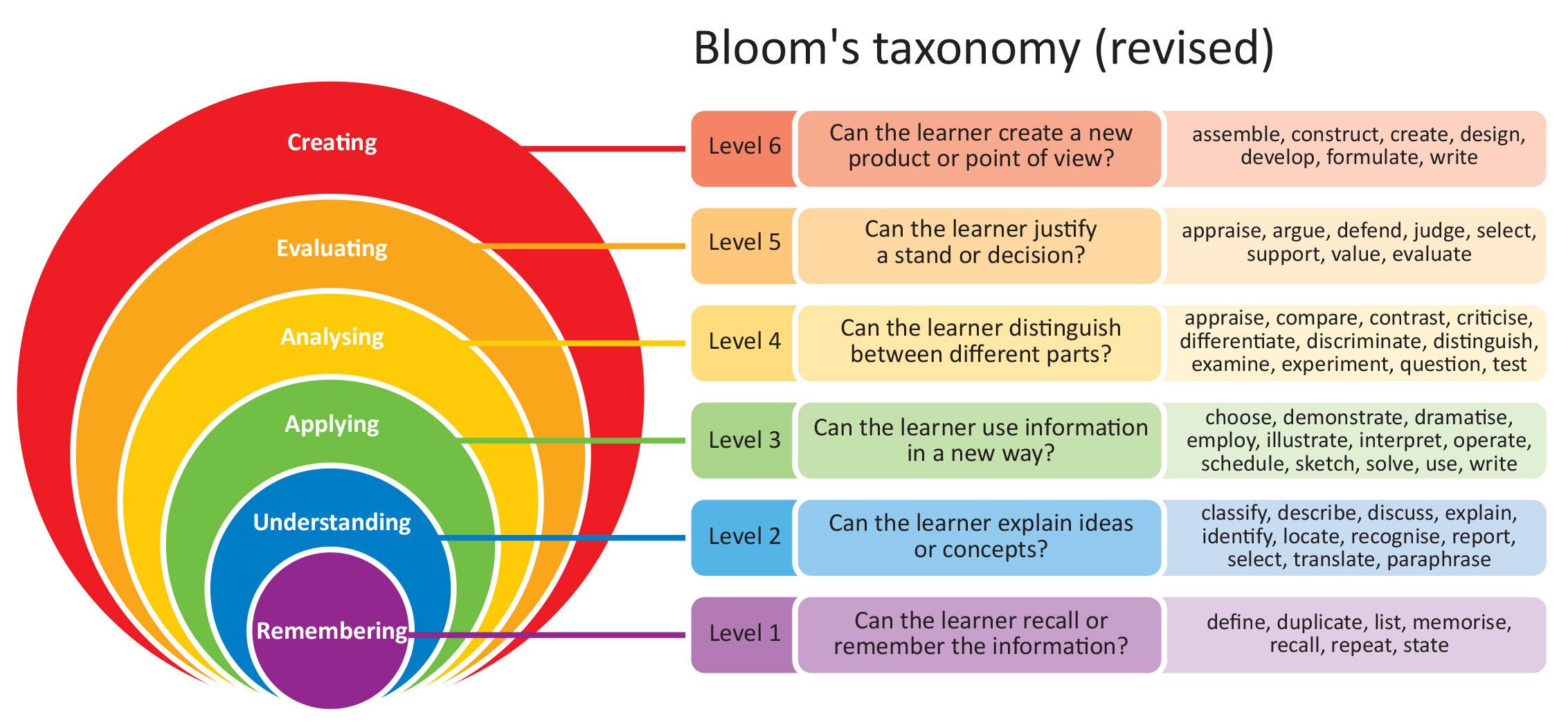

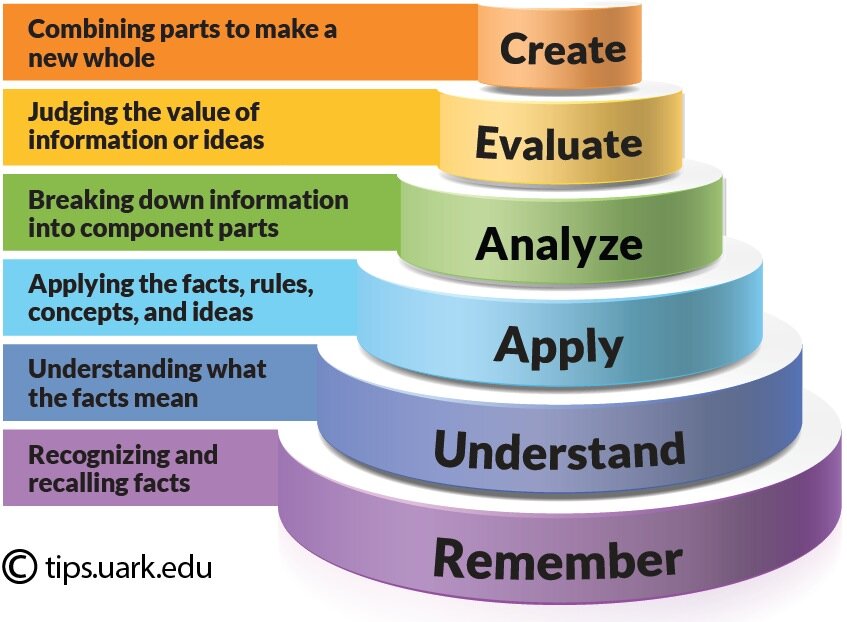

Learning outcomes are a great way to build scaffolding structure by using Bloom’s Taxonomy Pyramid. What are learning outcomes? Learning outcomes are a great way to show learners what they are going to learn in the teaching session and what they shall focus on for their learning purposes. Learning outcomes provide a strong backbone for the lesson and will demonstrate if the learners are on track. For example, learning outcomes can be used as exam questions, and if the students can comfortably answer these outcomes, then the knowledge was successfully transmitted. In a way, learning outcomes guide the learners to what they have to learn and the teachers to what they have to teach.

The learning outcomes must be clear, provide sound instruction, must be purposeful and guide the student to the expected standards. The learning outcomes can feature after the title of the lesson, for example, on slide 2 of a particular presentation. The learners will be introduced to the lesson with its title and will soon learn what is expected of them through the learning outcomes. When making learning outcomes, they must contain action verbs that describe what must be done. These could be: compare, describe, list, write, et cetera. Do note that a learning outcome can be done in a limited amount of time with a particular place. For example, “prepare a sterile field in a hospital ward setting under 3 minutes”. Avoid words that can have ambiguous meanings or words that are not precise. These could be: appreciate, enjoy, know, understand. Now compare these words to describe, contrast and compare.

Chatterjee D and Corral J (2017) mentions the use of SMART learning objectives, which is extremely important in terms of making relevant learning outcomes. These are:

(S)pecific: who will perform what actions? For example, a second-year medical student needs to perform a physical examination on a patient.

(M)easurable: the success needs to be measured; how will this be done? For example, the physical examination will have marks allocated for each section or part of the body being examined.

(A)chievable: with the available resource and the time frame given, can this objective be done? For example, do we have a patient, or is it a mannequin? Is there enough to go around for each student or must they share?

(R)elevant: is the method and assessment linking to the knowledge that has been shared by the teacher? For example, if first-year medical students are doing a physical respiratory examination on a patient, would it be relevant to them if they have not done any respiratory medicine modules?

(T)ime-bound: Is the amount of time given fair? Can the objective be done within that time frame? For example, to be able to do a physical examination under 8 minutes is generally the standard.

Interestingly learning outcomes can be classified into 4 main groups. These are: attitude, knowledge, performance and training. If we have to break it down, the learning outcomes for attitude teaches the learner to be more conscious and aware. For example, preparing a learning outcome on hand hygiene by making a learner do a written assessment on the importance of hand hygiene. Knowledge learning outcomes simply helps the learner knowing core and reliable knowledge. Performance learning outcomes are about skills and to be able to do these skills, such as a physical examination on a patient. Training learning outcomes are about making a product of what the school envisioned; for example, training medical students to become fully trained and ready for their intern years.

Building learning outcomes

How do we build robust learning outcomes? This is essential for a successful scaffolding technique by starting with learning outcomes that demonstrate the base of Bloom’s Taxonomy Pyramid. Necessarily, a teacher should start with key action words/verbs that are in the low or at the base section of Bloom’s Taxonomy, and slowly but surely, move toward the top of the pyramid. The learning outcomes considered as low represent passive learning or learning techniques that do not have the best efficacy in knowledge retention. The learning outcomes that are at the top of the pyramid represent active learning with the most success in transmitting knowledge. This is not to say that there should never be any low learning outcomes. Low learning outcomes are useful as they represent a base and a solid structure of the pyramid. However, the whole lesson/presentation needs to move from that base towards the top of the pyramid; hence the low learning outcomes are essential.

Below demonstrate some of Bloom’s work and how he manages to divide the learning into relevant sections with key action verbs. This is very useful when making the learning outcomes for a lesson.

If a teacher is presenting to a group of student in a time frame of 20 minutes, it would be fair to assume there could be 6 learning outcomes where 3 of the learning outcomes are considered to be ‘low’ and the other 3 as ‘high’. ‘Remember, understand and apply/application’ can be classified as low learning outcomes, and ‘analyse, evaluate and create’ can be classified as high learning outcomes. Below Chatterjee D and Corral J (2017) demonstrates the key action verbs per section on Bloom’s Taxonomy (adapted from the School of Medicine University of Colorado).

The table demonstrates the key action verbs that go into which sections in Bloom’s Taxonomy. From: the School of Medicine University of Colorado.

The illustration demonstrates, in a staircase style, the key action verbs that go into which section in Bloom’s Taxonomy. From: the School of Medicine University of Colorado.

Below is an example of 7 learning outcomes that each contain an action verb. These were added in a presentation that was 20 minutes long where the topic was about dyslipidaemia and its pharmacological treatments.

Define dyslipidemia.

List the main risk factors of dyslipidemia.

Describe the lipid transport system.

Compare and contrast the composition of Chylomicrons, VLDL, LDL and HDL.

Describe the mechanism of action of statins.

Explain the main adverse effects of statins and potential dangers.

Assess a case study and decide on an appropriate management strategy, including pharmacological interventions.

Here we have the key verbs: define, list, describe, which represent the lower-key verbs on Bloom’s Taxonomy. Compare, contrast, explain, assess and decide, are in the higher sections on Bloom’s taxonomy. A technique a teacher could use is that the learning outcomes become more and more intricate and complicated throughout the presentation. This was a technique that we used when we presented on dyslipidaemia as the beginning of the presentation, we used low learning outcomes such as defining dyslipidaemia. In contrast, towards the end of the presentation, we introduced a case study so that the learners could critically apply the gained knowledge and assess/decide on pharmacological interventions.

What is a Lesson Plan?

A lesson plan describes precisely how the lesson is going to be running. It is a useful tool in organising the lesson and seeing it as a whole. Teachers can then decide how much time will be allocated per slide or what pedagogy techniques are being used and when it is being used. Below is an example of what a lesson plan should look like. A lesson plan involves necessary information such as the name of the lesson, date, time and location. Having done my studies in South Africa, describing where the teachers are going to be teaching is crucial as sometimes the possibility to have a class with electricity or the internet may be a challenge.

Next, the aim and objectives describe what the primary goal of the lesson that is about to be given. What is the aim or purpose of providing this lesson? For example, we aimed to teach about the treatment of dyslipidaemia. The next questions should be, how much time do you have? This is a useful question as it will guide the teacher into how much depth they must go into. Teaching dyslipidaemia in an hour compared to 20 minutes has a huge difference in terms of details. The aim should reflect the outcomes you want to achieve. Are the outcomes being achieved? Who are the teachers teaching in the first place? Are the teachers teaching to medical students or high school students that have never heard the term dyslipidaemia?

The objective is similar to the aim. However, the objective describes how the aim is going to be achieved. This can be seen by what type of pedagogy techniques are going to be utilised, such as case studies or signpost presentation. How are these objectives being achieved? An example of an objective could be: make sure to go over the learning outcomes at the end of the presentation with the students. The teacher go over the learning outcomes and ask the class if they can now answer the learning outcomes. This objective will allow the teacher to hear direct feedback of their presentation and to make sure that they went over the learning outcomes at the end of the presentation.

The resource(s) is a simple checklist of what is being used in a lesson. This is quite important as recently a teacher was presenting on an important topic, and he/she forgot to charge his/her laptop. The teacher then asks for a charger, luckily somebody had a computer charger and on went the presentation (although it was pretty funny). Missing props or specific valuable resources could potentially end the presentation. However, sometimes a presenter will have to think on the spot and come up with a plan as outcomes or situations may be out of his/her control. For example, if a whiteboard was needed but on the day the staff forgot to bring a whiteboard, what should the teacher do next? Improvise, adapt and overcome.

Lastly, there is the session. Here, it is further divided into content, time, strategy and resources. This is a useful and effective way to see what information is going to be given, how much time is allocated for that information, what pedagogy strategy is being utilised, who speaks (if you re in pair) and what resources are being used. My colleague and I thought it would be a good idea to divide our session plan per slides so we could get a clear idea of what is going on throughout the presentation.

A lesson plan that we had to come up with. The lesson plan was very useful in organising our presentation and allowed us to see the big picture.

Making a rubric

Building a rubric is a crucial step in teaching and in a way, it allows rules to be set up. It allows feedback for the students as they can see where they did well and where they need to improve. A rubric also guides the students on what to do for an assessment as it provides support and a detailed description of each section. This is useful in terms of knowing where the mark allocations are and where to put more time and effort (such as word count) at different sections. A rubric provides feedback for the teacher in terms of seeing how their students are doing and coping with a certain assessment. Overall, a rubric provides standardisation across the students as each student will be marked upon what the rubric specifies. This is useful in terms of marking assessments, classify each student based on their assessment and deciding who gets a Pass (P) or a High Distinction (HD).

So what does a rubric need? A rubric needs criteria, descriptors and standards. The criteria divide the assessment into categories. This helps the students on what to focus when they are making their assessment. This could be introduction, description & context, evaluation & evidence, reflection & application, presentation & timing, academic writing, referencing, et cetera. The criteria depends on the type of assessment as a presentation will be different from a 2 000 word essay on novel drugs for Alzheimer’s Disease. The descriptors represent the quality that is required. This can go from a clear Fail to High Distinction where the descriptors becomes more and more complicated as the standard gets better. The standards are a range of performance going from Fail to High Distinction (although it can be anything). Below is table demonstrating the anatomy of a rubric.

This table demonstrates how a rubric would look like with the standards, criteria and descriptors.

How to develop a criteria

To develop a criterion, there is a need in identifying what type of assessment will be performed. Is the assessment a presentation, an essay or a live practical (such as involving patients). The criteria need to add up to 100% where each section needs to represent a percentage. These can be 5%, 10% or 25% per section with some variation. It makes sense that the sections with a higher percentage contain a higher significance in the assessment. For examples, references could represent 5%, and the main point of focus could represent 25% of the assessment. The criteria need to be easy to understand, concise and clear. Do not add too many criteria as it will stretch the assessment and do focus the criteria on learning outcomes.

How to develop standards

Standards help us to know what is outstanding or unacceptable, which provides set standards for each student. This should be straightforward as the standards are generally based on the institution guidelines. These could be Fail (0-49%), Pass (50-59%), Credit (60-74%), Distinction (75-84%) and High distinction (85-100%) or Fail (0-49%), Third-Class (50-59%), Lower Second-Class (60-69%), Upper Second-Class (70-74%) and First-Class (75-100%). Interestingly, a section of a standard can be further divided to allow the marker to decide and lean more on one side. For example, a Pass can be further divided into 2 sections where you get a Pass near Fail or Pass near Credit. The word fail could be replaced with unsatisfactory to avoid students feeling that they have ‘failed’ or that they are ‘failures’ themselves as this can have a psychological impact on the students.

How to develop descriptors

Descriptors are the hardest to produce, especially when these describe the standards in the middle. Describing the High Distinction and Fail/Unsatisfactory is reasonably easy as we would know what to expect with an excellent or poor assessment. The challenge is not to make the descriptors too easy or too hard but more as an even ‘bell curve’ so that it divides the students who provide an excellent piece of assessment from the not-so-good evaluation. As the standards are getting better, the descriptors need to slowly amplify in quality. Hence, there needs to be an extra description or becoming harder to achieve as the standards are getting better. Below is an example of an amplifying descriptor as the standards get better. Do notice that these descriptors only represents one criterion which is Academic Writing and Presentation.

Finally, why do we assess in the first place?

Assessments are a crucial part of teaching and presenting, and is a useful tool to demonstrate the quality of the teaching. Overall, an assessment gives direct feedback on how the teachers are delivering information and how the students are coping and understanding. Assessments should be given after a teaching lesson/presentation and should be reliable, valid, fair, challenging and manageable. These could include multiple-choice questions, case studies questions, short or/and long answer questions, oral presentations, and so on.

From a student point of view:

They get to see their feedback on how they are currently doing in a subject,

They get to see where they need to improve and understand a topic more,

They are getting used to be under high pressure such as writing an exam and use that resilience of being under pressure for their future jobs such as medicine,

They get to see if they are meeting expectations,

For some students that is where they get the motivation to study a topic which drives learning,

They get to build their skills through different assessments such as practicals, MSAT/OSCE, et cetera.

From a teacher point of view:

They get to see if their students are coping with the content and where they struggle. This leads to changing teaching techniques in a particular section or add/remove teaching styles. Hence, they get valuable feedback and see who might need support,

An assessment provides the ability to progress,

Ables the teacher to rank the students from each other,

Assessments, just like for the students, helps them to be motivated,

Justify that the medical students who were chosen are capable and that it was the right choice to select certain students.

Published 29th February 2020. Last reviewed 1st December 2021.

Reference

Anthony, G., & Walshaw, M. (2007) Effective pedagogy in mathematics. Ministry of Education; Wellington, New Zealand.

Bloom, B.S., Krathwohl, D.R., & Anderson, L.W. (2001) A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: a revision of Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman. https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/.

Brighton Authors. Assessment & Grading Criteria. University of Brighton website. https://blogs.brighton.ac.uk/askarchitecturedesign/coursework-and-assignments/assessment-grading-criteria/. Updated March, 2012. Accessed February 25, 2020.

Carmichael C, Callingham R, Watson J, Hay I. Factors influencing the development of middle school students' interest in statistical literacy. Statistics Education Research Journal. 2009;8(1):62-81.

https://researchoutput.csu.edu.au/ws/portalfiles/portal/8804244/PID28517postpub.pdf.

Classroom Authors. Factors That Affect Individual Learning. Classroom website. https://classroom.synonym.com/factors-affect-individual-learning-8207913.html. Accessed February 25, 2020.

Chatterjee D, Corral J. How to Write Well-Defined Learning Objectives. J Educ Perioper Med. 2017;19(4): E610. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5944406/.

Colorado University Authors. Guidelines for Writing Learning Objectives. Colorado University School of Medicine website. http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/medicalschool/education/degree_programs/MDProgram/administration/curriculumoffice/Documents/CUSOM_Learning-Objectives-Guidelines.pdf. Updated December 1, 2019. Accessed February 27, 2020.

Cornell Authors. Center for Teaching Innovation: Using Rubrics. Cornell University website. https://teaching.cornell.edu/teaching-resources/assessment-evaluation/using-rubrics. Accessed February 25, 2020.

Darlo Authors. Malcolm Knowles’ 6 Adult Learning Principles. Darlo website. https://darlohighereducation.com/news/malcolmknowles6adultlearningprinciples/. Updated November 3, 2016. Accessed February 26, 2020.

Knowles, M. The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species. 3rd ed. Houston: TX Gulf Publishing.

Mubuuke AG, Louw AJN, Schalkwyk SV. Cognitive and Social Factors Influencing Students׳ Response and Utilization of Facilitator Feedback in a Problem Based Learning Context. Health Prof Educ. 2017;3(2):85-98. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2452301116300335.

Nilsson, S., Pennbrant, S., Pilhammar, E., & Wenestam, C. (2010, January 28). Pedagogical strategies used in clinical medical education: an observational study. BMC Med Educ, 10(9). 10.1186/1472-6920-10-9.

Ramsden, P. (2003) Learning to teach in higher education (2nd ed.). London: Routledge Falmer.

Shubham D, Biro P. Exploration of Factors Affecting Learners' Motivation in E-learning. IJSRCSEIT. 2019;5. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336285085_Exploration_of_Factors_Affecting_Learners'_Motivation_in_E-learning.

Surrey Authors. University of Surrey Grade Descriptors: Undergraduate Programmes. University of Surrey website. https://www.surrey.ac.uk/cead/resources/documents/University_of_Surrey_Grade_Descriptors.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2020.

ADDITIONAL SOURCE OF INFORMATION:

Christopher Pappas. The Adult Learning Theory - Andragogy - of Malcolm Knowles. E-learning Industry website. https://elearningindustry.com/the-adult-learning-theory-andragogy-of-malcolm-knowles. Updated May 9, 2013. Accessed February 26, 2020.