Standardised Mini-Mental State Examination: What Is It About and How Is It Done?

Introduction

Published in 1975 by M. F. Folstein et al, the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a tool to evaluate the cognition of an adult and assess if there is any impairment. By 1997, in order to increase reliability and reduce variability, Dr D. William Molloy and Timothy I. M. Standish developed the Standardised Mini-Mental State Examination (SMMSE) which provided simple but detailed scoring instructions and reduced any ambiguity from the MMSE. The SMMSE tool is particularly useful for patients complaining of memory loss or exhibiting loss of cognition and/or signs of dementia. The SMMSE tool and its guideline have been granted by the copyright owners, Dr D. William Molloy through the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority (IHPA), to be used freely in the Australian health sectors. If you are outside of Australia, please ask Dr D. William Molloy for his consent to which I am confident he would agree.

Why is this relevant?

Around the world, there is a need to increase the expenditure in development and research of dementia. Statistically every 3 seconds, one person is developing dementia which 60-70% of the cases are diagnosed as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Another worrying fact is that the number of people with AD will triple by 2050. The latest World Alzheimer Report has demonstrated that there are not enough publications of neurodegenerative disorders and compared to cancer publications, there is an astounding 1:12 ratio. It is also noted that there are not enough people going into dementia research as there has not been any significant breakthrough in the past 40 years.

In the United States, as the population age increases, there has been a significant increase of 145% in Alzheimer’s death whereas it has been reported that the number one cause of death (heart disease) has decreased by 9%. Hence, it is essential to recognise the early signs of dementia where the SMMSE is proven to be particularly useful in testing cognitive impairment and for clinical trials criterion.

The Standardised Mini-Mental State Examination

The Standard Mini-mental State Examination (SMMSE), compared to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), takes less time and has less variability in rating between physicians. The SMMSE should run for about 10.5 minutes and does not require extensive training from the health care staff. The test seems simple but tests critical neurological criteria and cognitive domains such as orientation to time and place, short and long term memory, registration, recall, constructional ability, language and the ability to understand and follow commands.

To make a sound diagnosis, it is always a good idea to not utilise the SMMSE alone but in conjunction with a thorough History Taking (which includes chief complaint, SOCRATES, current medication treatment, past medical history, past surgical history, social history, SNAP and family history), Mental State Examination and the 4P Factor Model.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) and Dementia Australia mention other techniques for case findings and diagnosis confirmation, these are:

Asking ‘How is your memory?

Drawing a clock.

Using the Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale is useful for multicultural cognitive assessment and dementia across cultures.

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients, the Kimberley Indigenous Cognitive Assessment tool (KICA) dementia assessment instrument may be used.

The DementiaKT hub is useful for other tests and physicians.

Who should be tested?

Any patients that are above the age of 65 years old or any patients that are anxious about losing their memory as Early Onset Dementia is a real potential risk. The test should be done opportunistically or when the patient fits the criteria. A physician should always be aware of any signs and symptoms of dementia and should be aware that depression and dementia co-exist.

There are no benefits to screen when patients show no symptoms or complaints. Those who are at moderate risks early interventions should be done. These are patients that present with symptoms of dementia and other cognitive problems, family history of dementia and AD, repeated head trauma, patients with cardiovascular diseases or risks (including diabetes, smoking et cetera), low education status, hearing loss (occurred during midlife), depression, physical inactivity and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Depression or Dementia?

What is difficult about the SMMSE, which was a topic in the Understanding Dementia (MOOC), is the fine line between what becomes an abnormal change in cognition versus normal memory loss or normal decrease in cognition due to ageing. Of course, when the results are clearly in the range of early stage of dementia, the physician can be confident in his diagnosis (along with other tools).

It is difficult to differentiate between dementia or depression as they show similar symptoms and may co-exist; however, there are differences between dementia and depression. Another challenge is to differentiate patients that are confirmed with dementia if they have depression or not; further investigation needs to be done. Below are the main difference between dementia and depression.

Dementia

Onset: months to years, the onset of symptoms is only known within broad limits.

Mood: fluctuates, suicide or sense of guilt are rare.

Course: chronic, slow and irreversible deterioration over time.

Self-awareness: likely to hide or unaware of decline.

Daily living: may be intact at first, slowly becomes worst as the disease becomes worst.

Depression

Onset: weeks to months, the onset of symptoms can be dated accurately.

Mood: low or apathetic, suicide or sense of guilt are common.

Course: chronic, responds to treatment.

Self-awareness: likely to be concerned about memory impairment.

Daily living: may neglect basic self-care.

Before the test

Having practised an SMMSE during an exam (MSAT/OSCE) to a patient, it is an awkward interaction if you are not prepared. The patient must feel comfortable, must be seated in front of the speaker and be able to hear and understand well. Make sure there isn’t any apparent syndromes or cognitive impairment which does not allow a normal conversation or understanding simple instructions. Does the patient understand the language being spoken? Does the speaker have an accent, and is it easily understood? Does the patient have hearing aids?

Just as usual, introduce yourself and gain consent for the memory test (SMMSE test). Being comfortable and confident is essential for this interview as well as clear pronunciation. There are some rules when giving the test. The questions may be repeated to a maximum of three times, and if the patient still does not answer then allocate a zero as a mark. If the patient answers incorrectly, then allocate a zero (depending on which questions, making a mistake does not necessarily mean a zero). If the patient replies with “what did you say?” then repeat the question to a maximum of three times. Do not explain and do not engage, just repeat. If the patient interrupts because they don’t understand, then calmly reply that it will soon be over and that you will explain in detail about this test.

A challenge during the test is keeping a ‘poker face’. Avoid hints, physical movements on the face, nodding, head shaking or making any sounds. Whether the patient got the question right or wrong, accept the answer and move on to the next one.

Equipment required before starting the test:

Watch,

Pencil,

Piece of paper for the patient to write down a sentence,

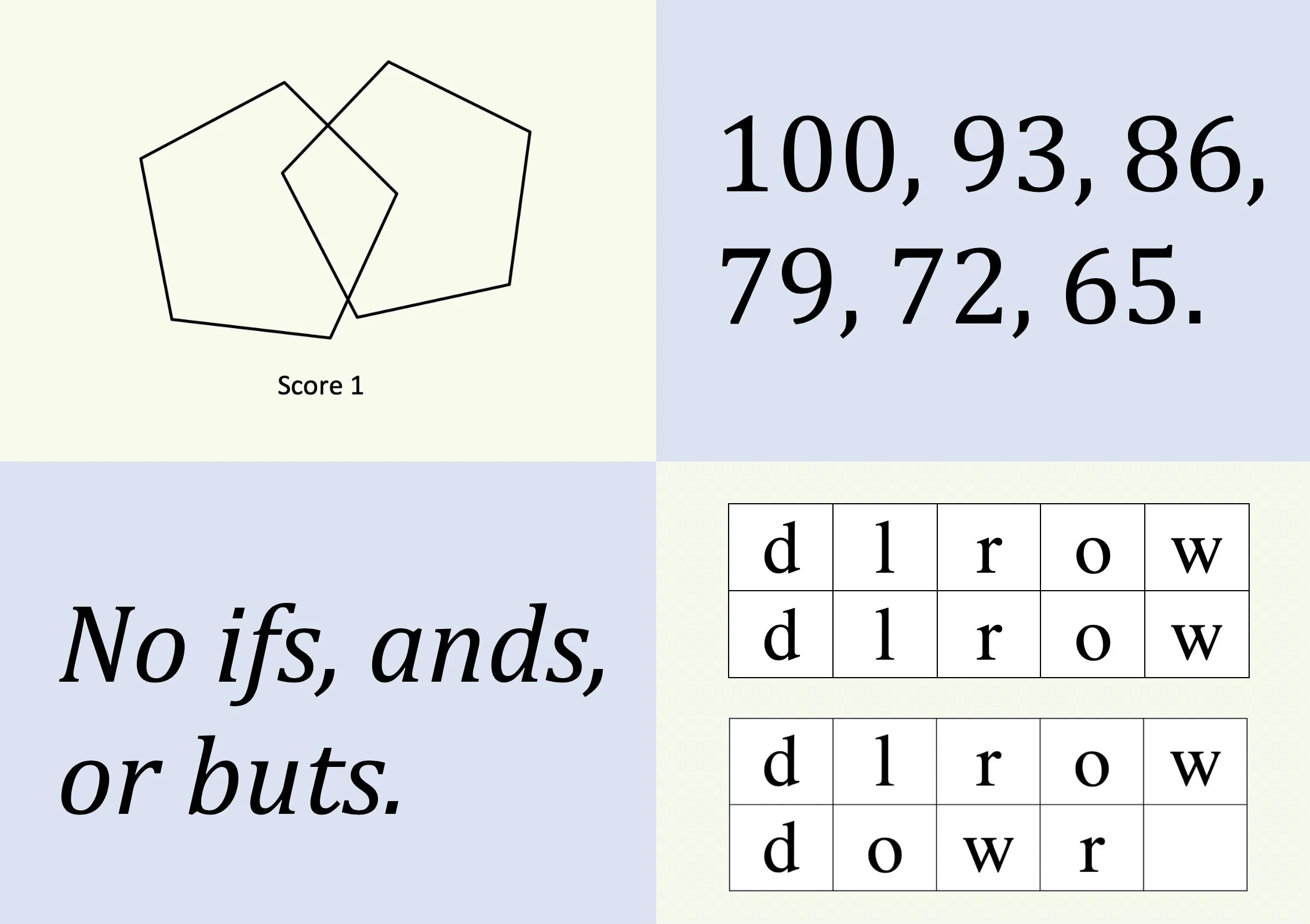

On a piece of paper draw two five-sided figures which intersect making a four-sided figure,

Behind the SMMSE score sheet or on a piece of paper write in large letters CLOSE YOUR EYES,

Do know the season you are in, the month, today’s date and the day of the week.

Make sure the CLOSE YOUR EYES and the drawing or not shown together at the same time as this may cause confusion. Be aware that there is a specific way to score the WORLD backwards, the serial sevens and the overlapping pentagon.

The test and scoring

Below is the SMMSE tool and the Instruction Guidelines:

Adjusting the scores

It should be said that scoring fairly is crucial. Sometimes patients who are physically unable to do specific tasks such as folding the paper should not be scored lower. Try to do to change the exercise to ‘take the paper in your hand, crumble the paper and throw it on the ground’. In these particular situations where a patient is clinically blind or has difficulty reading, the task can be removed from the test and the points can be removed from the total score. See the SMMSE Guidelines to see the equation for the readjustments for the new score. Remember to round up or down if you get a fraction.

If there is a disability that is not permanent, wait for the patient to recover, however, if it takes too long as it could be months then assess the situation and decide when to give the test. In Australia, there are many of patients who don’t speak English as their first language. It is important to differentiate between not understanding the questions due to language barrier or cognition impairment. In particular conditions try to get a translator or the SMMSE in their own language. Again, check if there is a hearing impairment.

Some patients may have speech impairments. Unfortunately, the test will be biased for these patients as there are time limits. The keynote is to stay consistent and use the SMMSE with other tools for a proper diagnosis. A low education could also impact the SMMSE such as if a patient does not know how to read, formulate sentences or count to 100 (let alone subtract 7 from 100). Make a note of this and stay consistent.

Below is the SMMSE scoring table which contains the guideline of where the patient potentially is in regards to his/her cognition. It is important to note that each patient are unique, and there are many variabilities. The literature, as well as the Understanding Dementia (MOOC) from the University of Tasmania Dementia Research & Education Centre, agree that thorough family history and getting as much context of what is happening in your patient’s life is crucial in determining if there are developing dementia.

The SMMSE total scores are correlating to the stages of dementia disease and areas of impairment in Alzheimer’s Disease. Found in Standardised Mini-Mental State Examination (SMMSE) Guidelines for administration and scoring instructions.

Intervention and prevention

Although developing dementia is mainly unknown, 35% can be modified and change for the better. The risk factors and outcomes are different for everybody and the non-modifiable factors such as age, genetics and family history cannot be changed. It is never too early to start changing what we can to reduce or delay the onset of dementia.

There is strong evidence in the literature that preventing cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension, high cholesterol, type 2 diabetes and obesity have a substantial impact on reducing or delaying the development of dementia. Eating healthy such as a Mediterranean diet and avoiding processed foods, exercising and reducing or ceasing entirely smoking are aspects patients can change. The RACGP recommends 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity walking or other activity is beneficial and is proven to improve and reduce dementia risks. Having proper sleep techniques and hygiene as well as protecting your head at work or during sports game is vital. Do check up on mid-life hearing loss with a physician as it has been linked as a risk for dementia. Another activity patients can do to look after their mind is to practise brain exercises such as learning new hobbies or languages, play games and puzzles, and socialise with other people.

Below is a table from The Lancet about the risk factors for dementia.

Acknowledgement

The SMMSE tool and its guideline have been granted by the copyright owners, Dr D. William Molloy through the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority (IHPA), to be used freely in the Australian health sectors. If you are outside of Australia, please ask Dr D. William Molloy for his consent.

Published 20th May 2020. Last reviewed 1st December 2021.

Reference

Alzheimer’s Association. 2019 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figure. Alzheimer’s Association website. https://www.alz.org/media/documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures-2019-r.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed August 29, 2019.

Alzheimer's Association Authors. Early Onset Dementia a National Challenge, a Future Crisis. Alzheimer's Association website. https://www.alz.org/national/documents/report_earlyonset_summary.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2020.

Dementia Australia Author. Depression and dementia. Dementia Australia website. https://www.dementia.org.au/national/support-and-services/carers/behaviour-changes/depression-and-dementia. Accessed May 12, 2020.

Frankish H, Horton R. Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care. The Lancet website. https://www.thelancet.com/commissions/dementia2017. Published July 19, 2017. Accessed May 17, 2020.

Independent Hospital Pricing Authority Authors. Standardised Mini-Mental State Examination (SMMSE). Independent Hospital Pricing Authority website. https://www.ihpa.gov.au/what-we-do/standardised-mini-mental-state-examination-smmse. Accessed May 12, 2020.

Patterson C. World Alzheimer Report 2018: The state of the art of dementia research, new frontiers. Alzheimer’s Disease International website. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2018.pdf. Published September, 2018. Accessed August 29, 2019.

Royal Australian College of General Practitioners Authors. Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice: The Red Book, 5.5 Dementia. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners website. https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/red-book/preventive-activities-in-older-age/dementia. Accessed May 12, 2020.

World health organization. Dementia. World health organization website. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia. Updated May 14, 2019. Accessed August 29, 2019.